LOWELL DARLING

How I Learned to Draw

November 8 – December 6

Opening reception and book signing: Saturday, November 8, 3:00 to 7:00 pm

Random Parts is pleased to present How I Learned To Draw, a solo exhibition by Californian conceptual artist, Lowell Darling.

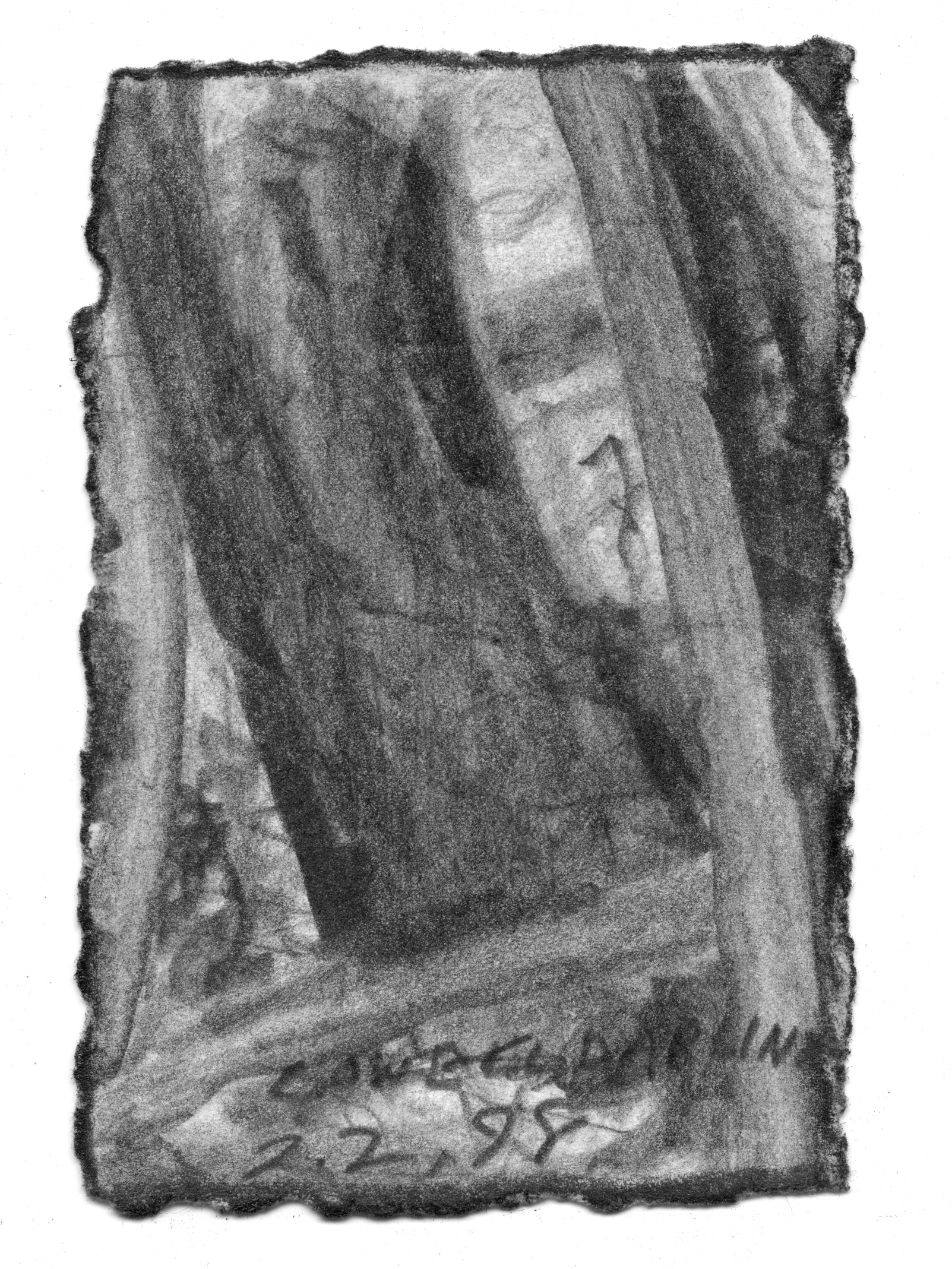

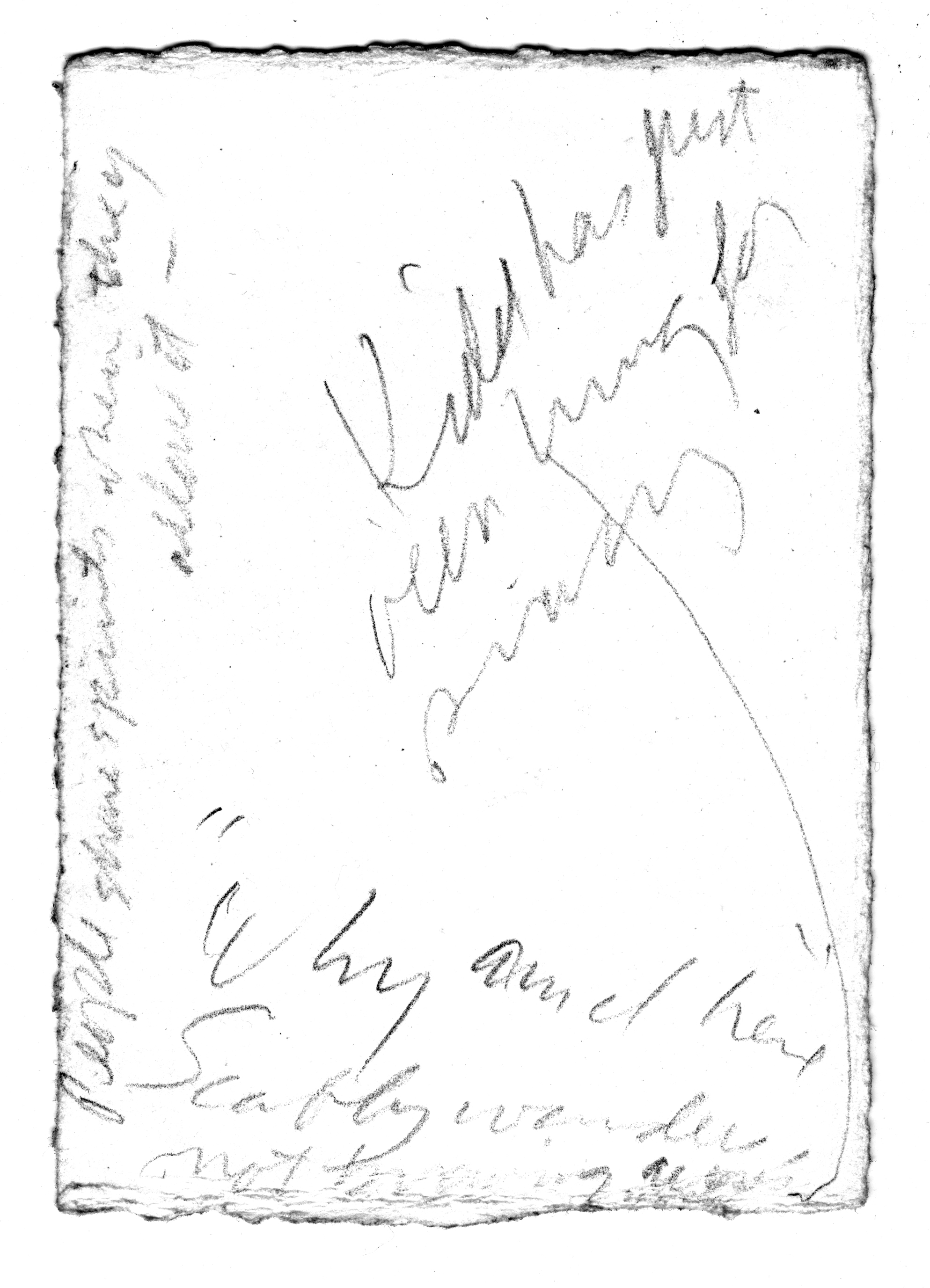

For his show at Random Parts, Darling will focus on two series of drawings – his collaborative drawings with his daughters and his Shirt Pocket Forest Drawings. The former is a collaboration with his two daughters, Sophie and Ruby Darling, that date back from the early 1990’s when the girls were young children. Acting as an “art fairy”, Darling would color in the drawings while the girls slept. During this same time, Darling started to make his Skull Field Drawings based on his daily walks in the Sonoma County forest. At Random Parts, Darling will show his series, Shirt Pocket Forest Drawings, an intimate group of smaller drawings from the Skull Field Drawings series.

Lowell Darling is known for his conceptual art from the '70s onward which include such notable works as Urban Acupuncture, running for governor of California in 1978 and 2010, starting an art school, Fat City School of Finds Arts, and the Hollywood Archaeology series just to name a few. He has exhibited in museums and galleries globally, including most recently Under the Big Black Sun: California Art 1974–1981, Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, and State of Mind, New California Art Circa 1970, that traveled from Orange County Museum to the Berkeley Art Museum.

For more information on Lowell Darling, please go to www.lowelldarling.com

During the opening reception, Darling will be available to sign his new book, Skull Field Drawings, published by CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. A limited number of books will be available for purchase at the gallery.

Drawing was my escape as a kid. I wanted to be Norman Rockwell, Walt Disney, Max Fleisher, or Rockwell Kent (gasp!) As a teenager I wanted to be Franz Kline, Joan Mitchell or Jackson Pollock. At twenty-one I lost an eye and turned to clay to let my hands make up for lost depth perception.

In 1968, after my first gallery show (Pollock Gallery, Toronto) the IRS said I wasn’t an artist because I didn’t sell enough art. In retaliation I quit making objects, focused on solving world problems, and started making news, having mastered the art of the press release. The press always stated I was an artist, proof to show the IRS. I won my case in 1975. I attempted to culminate my pro bono public media practice by running for Governor of California in 1978.

During the 1980s I was depressed and made little art until I had children late in the decade. My daughters loved to draw. I would color in their drawings at night while they slept, becoming the art fairy. This took me back to where I began, pushing lines and color around just because it was fun and made them happy. At this same time I was telling my kids bedtime stories every night. I began to see rocks and trees and shadows on my daily walks in the forest that looked like characters in my stories. I began to draw these things and create a mythology about them.

Today I draw and write and do little else. (Other than my recent project to save the world: Hands On Healing Earth Day; January 1, 2015: At noon, wherever you are, go outside and place your palms on the earth. Pass it on. Tell your local media what you are doing.)

THERE IS A STORY behind the drawings in this book. It begins with a confession. I had hit a point where the art I needed to make had been made. Everything I had to say had been said. I was uninspired and went into exile, moving to the country, but I still maintained a studio. The studio was built on a former cattle ranch where the soil harbored an olfactory hint of its former inhabitants. On the hill beyond this perfumed pasture stood a remnant of Redwood forests that once covered West Sonoma County. I would sit in my new studio, looking out the windows, wondering what to do. Then one afternoon I decided to forget everything and take a walk, crossing the pasture and following the animal trails into the trees. The trail crossed two noisy creeks before leading into the forest, where the temperature dropped like entering a dark air-conditioned theater. Upward and westward the trail meandered through hushed coolness. Silence made the forest seem empty. The only sounds were my feet stepping on leaves and breaking twigs. I had not yet learned to walk quietly and listen. Seldom had I felt more alone — not even when sailing across the ocean when young. As I walked out of the forest, however, back into the meadow, I discovered I was not alone. Above my head circled a brilliant Red Tail Hawk, and not in silence did it fly. The sound of its wings broke the air when it dived at me, and I whistled shrilly in return—almost a scream of joy. The hawk’s dive was so magnificent and thrilling, I longed for wings. From that day on, whenever I walked across the pasture, the Red Tail Hawk would join me. If the sky was empty when I left the studio, I could whistle and the Red Tail Hawk would come, circling above my head, calling back to me, diving like a feathered rocket. Some days the hawk came from the top of a tall dead Fir that stood on a neighboring hill. Sometimes it came from trees that grew between where I entered and exited the forest. Sometimes it came out of nowhere. Curiosity caused me to begin making small map-like sketches, drawn only to note from whence the hawk came. Eventually these rough sketches led me to a dead tree fallen across my trail, deep in the forest. Above this fallen log, high in the trees, I saw a nest. I could only assume this nest was the reason for the Red Tail’s aggressive behavior, and I didn’t linger. I, too, was a protective first-time parent. Days later, perhaps a few weeks after I began drawing again, I saw the white hawk take its first flight with its mother. At first it crashed noisily through the branches, crash landing next to my trail, not twenty feet from where I stood. I could hear its parents calling excitedly from above the foliage and hastened out of the trees into the open pasture where the nervous adults could see me. There I watched the drama unfold above my head, witnessing the first flight of the Red Tail chick. Now all three birds were circling my head. The new hawk flew like a clumsy puppy walks, or a newborn calf. For a few weeks all three hawks greeted me when I entered the pasture outside my studio. They performed their acrobatics above my head and called back when I whistled at them. Then suddenly they were gone. The nest was as empty as the sky. I knew that by autumn their nest would be taken over by owls.

-Lowell Darling